From L5 News, March 1982

(The L-5 Society is rapidly gaining recognition as the most effective pro-space organization, as witness this report copyrighted 1981 by Industrial Research & Development magazine, reprinted by permission — ed)

In late 1979 the United Nations drafted and approved a treaty that would establish guidelines on future uses of Earth’s moon and outer space. This controversial “Moon Treaty” elicited heavy opposition from U.S. business and scientific communities because, critics charged, it would have prohibited commercial development in outer space and would have “socialized” future lunar and planetary bases and space stations.

The Carter administration was in favor of approvung the treaty. But with the election of Ronald Reagan the Moon Treaty is a “dead issue,” according to administration officials and Congressional sources. President Reagan does not plan to submit the treaty for ratification to the Senate and, even if he did, there is a consensus that the Foreign Relations Committee would not pass it. “The danger is over,” said one informed Senate source. “It’s not going anywhere so nobody has to worry about it.”

The disputed treaty is formally known as the “Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.” It was adopted by the U.N. General Assembly without opposition and without vote in December 1979. Before it becomes legally binding for the U.S., however, the Moon Treaty would need to be signed by Reagan and ratified by the Senate.

The treaty, which industry critics termed “a giveaway of unprecedented proportions,” draws heavily on language incorporated into the still-unsettled Law of the Sea Treaty. The Moon Treaty, for example, designates the Moon and its resources as the “common heritage of mankind” and calls for the establishment of an “international regulatory regime” to create and oversee an equitable system to share resources once the means of lunar exploitation becomes feasible. That, critics in the R&D industries and in the Senate charged, essentially means private industry would be prohibited from developing outer space.

United Technologies Inc., the Aerospace Industries Assoc. (AIA), and other groups have opposed aspects of the Moon Treaty. The L-5 Society — a group of scientists, engineers, and “concerned citizens” — last year lobbied the Senate and the White House extensively against the treaty.

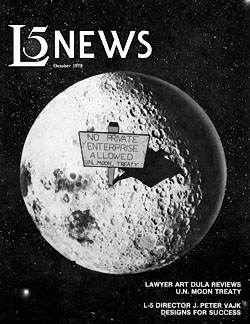

The L-5 Society published this cover on the L5 News in October 1979, early in its campaign to renounce the “Moon Treaty.”

As a result of the opposition generated by these private groups and a growing wariness of the treaty expressed by some members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the Carter administration last year put the pact on hold and established an interagency committee to review the treaty and seek a compromise.

“That interagency committee never submitted its report,” said David Small, a State Dept. attorney familiar with the Moon Treaty. Added a White House official, “After Reagan was elected, the administration gave serious notice that it was against the Moon Treaty and the Law of the Sea Treaty.” While neither the administration nor the Senate has taken an official position on the Moon Treaty, insiders explain that there is every indication that by their not actively moving forward with ratification, the treaty is essentially dead.

Part of the opposition to the treaty lies in the fact that “the smaller countries of the world, which compromise less than 20% of the wealth or power, in effect would be in a position where they could attack those countries or companies that went out and developed” the Moon or outer space, said Mark Hopkins, executive vice president of the L-5 Society.

“The Reagan administration has not formally said anything,” Hopkins told IR&D. “However, we know the people that are in charge of this sort of thing at the State Dept., and we have the utmost confidence that they are not going to sign it.”

An informed Senate source explained that even prior to the elections, some members of the Foreign Relations Committee took the position that they were opposed to the treaty. “I don’t think that has changed,” he said. “I suspect that the views expressed then are pretty much in line with the philosophies of the present Senate.

“But the key is not how the Senate Foreign Relations Committee would react; it’s whether the Reagan administration would ever agree to go along with it. I sort of doubt they would in light of what they’ve done with respect to the Law of the Sea,” he said.

Earlier this year the administration announced it would temporarily block completion of the Law of the Sea Treaty, which was scheduled for final deliberations after more than six years of effort. Officials told the Senate that there were serious problems with the Sea treaty, especially with provisions that would limit production of manganese nodules from the deep seabed and mandate creation of a global revenue-sharing fund to distribute profits from such mining. Both the Law of the Sea and the Moon Treaties term their respective resource areas the “common heritage of mankind.”

Some critics of the Moon Treaty foresee a possibility of compromise. One approach would be to “try to negotiate a treaty which will allow free enterprise to operate in space and also put together some sort of governing body for resources in space.” Hopkins said. “In this way, each nation that’s invoked in it would have a voting strength proportional to the level of investment they put into it.”

Whether such a proposal would seriously he considered by the strictly egalitarian U.N. is questionable, others say. And at this point many are comfortable with the prospect that the Moon Treaty seems destined to remain on the back burner, at least for the foreseeable future.